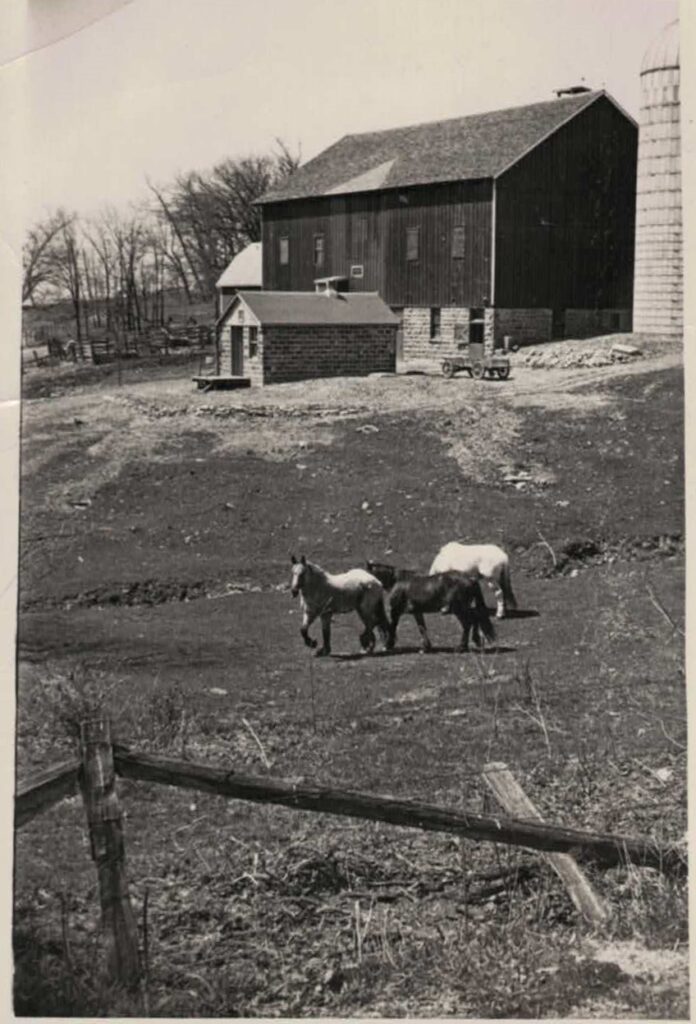

It all began in Blue Mounds, Wisconsin at the Brigham Farm.

The Brigham Farm was a continuation of the homestead created by Ebenezer Brigham in 1828 when he first arrived in what is now Blue Mounds. When Brigham settled here, he had no idea that a cave lay just beneath the surface, and that cave would sit in darkness for another 111 years before being discovered.

After Ebenezer’s death, his land was given to his brother’s children, and it was eventually used by Charles Brigham, Sr. as a dairy farm. He kept purebred jersey cows–though he was known to keep pigs and sheep as well–and was also the first to keep scientific dairy records in Wisconsin. These records caused the family to develop a close relationship with the Department of Agriculture and University of Wisconsin – Madison.

In 1903, a small quarry was opened on the farm’s hillside. While originally just for the farm’s use, geology students from the Universities of Wisconsin and Chicago–and even the 1935 Kansas Geological Society!–would visit to study fossils and bedding layers, wholly unaware of the geologic wonder beneath their feet.

In 1939, the usage of the quarry was leased to a contractor hired to supply crushed rocks for the Dane County Highway Department. On August 4 that year, quarry workers prepared for another blast to harvest rock. Lance Dodge, the well driller, drilled eight holes 25ft into the ground, but the final three holes dropped 30ft deeper than expected, convincing Dodge that there may be a cavity beneath them.

Despite the curious cavity, Dodge proceeded with the blast, loading 1,600lbs of blasting powder into the holes and setting it alight. In total, over 5,000 tons of rock were thrown into the air.

When the dust settled just after 11:00am, two gaping holes sat in the face of the quarry. Forty feet of the cave’s ceiling had been ripped away, revealing a dark cavity of unknown depth. The glass-like sound of cave formations shattering caused the workers to believe that there may have been people within the cave, but later exploration proved that the cave was undiscovered and uninhabited.

“When I arrived at the scene of the blast, the crowd was still on top of the cliff looking at the two gaping holes. No one had yet dared to climb over the rocks and look into the cavities.” – Charles Brigham, Sr.

Originally planning to wait three days before entering the cave, four men descended into the cave a mere three hours after the discovery after Lance Dodge brought flashlights from town, and his son-in-law Wayne Lampman was the first to enter. Charles Brigham, Jr. went down second, followed by Stacy Collins–a dairy farmer who worked at the Brigham farm–and then Lance Dodge himself.

Following the natural pathing of the cave, they traveled south through the large cavern before being impeded by a blockade of fallen rock at the end of the passageway. Early the next morning, Lampman, Brigham Jr., and Dodge returned to the cave to explore the northern passage, making it as far as the area now known as the “Narrows.”

Upon their return, they confirmed that there were no other entrances into the cave, and that they were truly the first to ever see the cave; however, they soon wouldn’t be the only ones to ever see it: word of the discovery was spreading quickly. Charles Brigham, Sr. sealed the entrance with wood and stood guard over the hole to prevent vandalism.

“Everyone is crazy to get into [the cave]. Stalactites & Stalagmites of limestone. Lovely- Charles so excited.” – Rosanna Gray Brigham, wife to Charles Brigham, Sr.

Soon after the discovery, two local businessmen–Carl Brechler and Fred Hanneman–made and won their bid to develop the cave into a tourist destination. They created a plan to make the cave easily accessible for young and old, big and small. These men–a bank teller and a band director, respectively–worked tirelessly along with their families to develop the cave into a tourist destination.

The cave was officially opened for tours on May 30, 1940, just nine months after the initial discovery and just in time for Memorial Day weekend. Within the first twenty-seven weeks of being open, more than 58,000 visitors came to see the cave. For these guests, the entire tour was: “Cave of the Mounds was discovered accidentally on August 4, 1939. Enjoy your tour.”

Today, we know a lot more about our underground wonder.

The cave was managed briefly by famed archaeologist and speleologist Alonzo Pond, who wrote for us the Illustrated Guidebook of the Newly Discovered Cave of the Mounds (1941), the first geological publication for the cave. Since then, many studies have been conducted at the cave, furthering our understanding of the strange world that lies beneath our feet.

In 1988, Cave of the Mounds was designated a National Natural Landmark by the Department of the Interior and the National Park Service for its illustrative character, rarity, and value to science and education. While we are not technically a national park, this designation affords us a valuable distinction as one of the great examples of geology and nature in Wisconsin.

These days, we are visited by over 100,000 people each year who come to see the cave, walk our ever-growing trails and gardens, and crack geodes or discover treasure at the gem & fossil sluice. The geologic curiosity is continued daily by our guests–big and small–along with our ongoing research projects. Though the cave was discovered nearly 100 years ago, we still honor the decades of history that came before us each and every year during our Discovery Days celebration.