The geologic story of Cave of the Mounds begins…

with the formation of its host rock. The rock that the cave formed in is limestone, a soft sedimentary rock that forms from cemented shells, corals, and sediment like mud or clay. It is the bedrock of this part of Wisconsin, and it formed over 450 million years ago in the Ordovician Period.

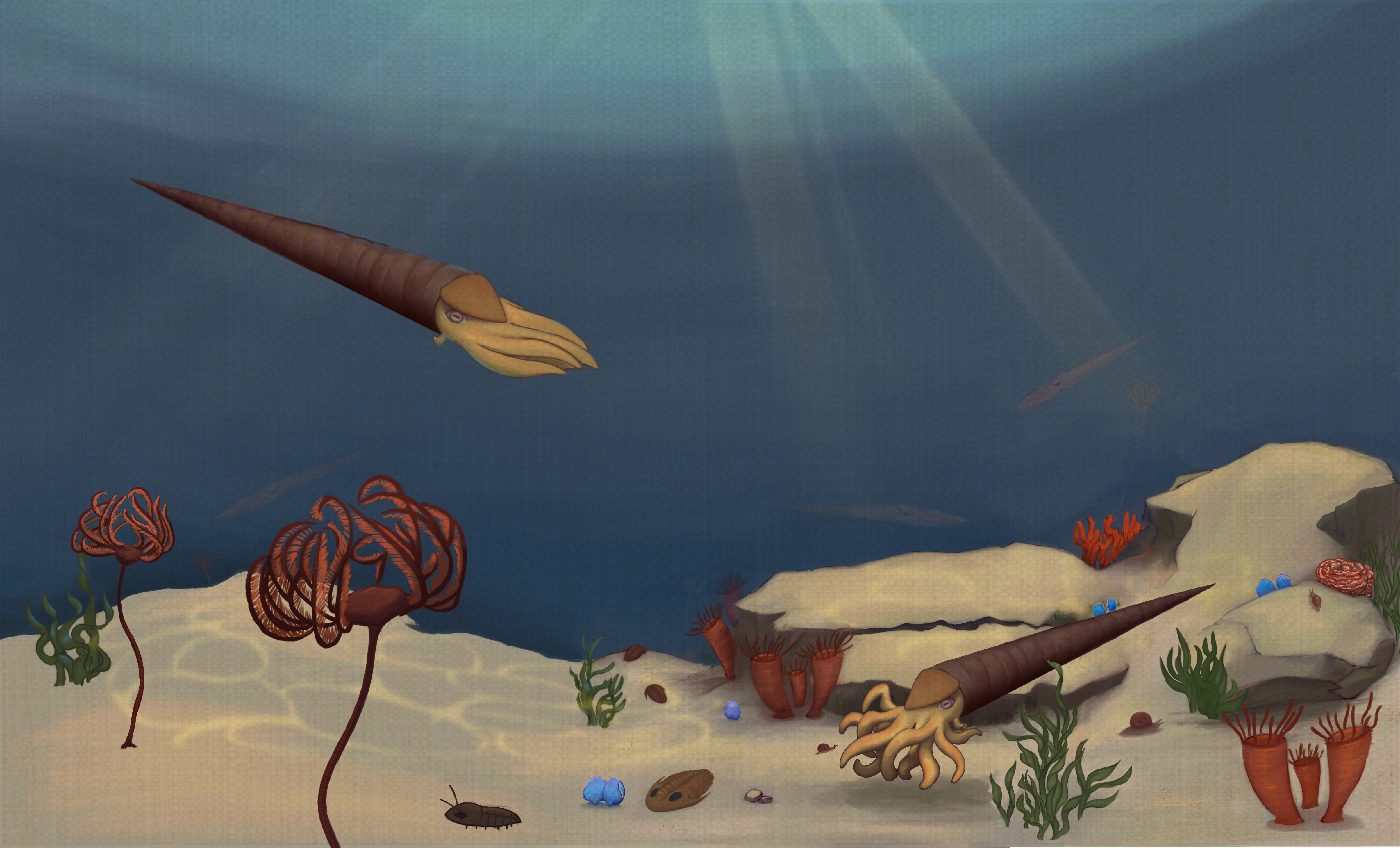

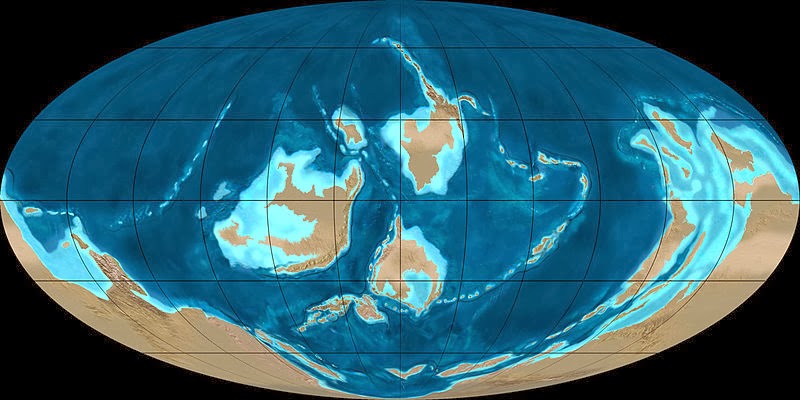

DURING THE ORDOVICIAN PERIOD, North America was further south by the equator, and Wisconsin was covered in warm, shallow seas. These seas were teeming with creatures that built their shells and bodies out of calcium carbonate, the main ingredient used to create our limestone.

Thousands of feet of limestone were deposited by these shallow seas all across the globe, making it incredibly common: around 20% of all sedimentary rocks on Earth are limestone!

AFTER MILLIONS OF YEARS, the vast waters that covered North America receded as the continent was uplifted, exposing these rock layers to the erosive forces of nature. A caprock made out of chert–an incredibly hard sedimentary rock–formed on top of our limestone and protected it from being eroded away in this area. This not only made the Blue Mounds the highest points in this part of the state, but it also allowed the cave to exist. Our limestone also began to change: calcium carbonate shifted into magnesium and created Galena Dolomite, a slightly stronger form of limestone. Within this rock, Cave of the Mounds began to form 1-2 million years ago.

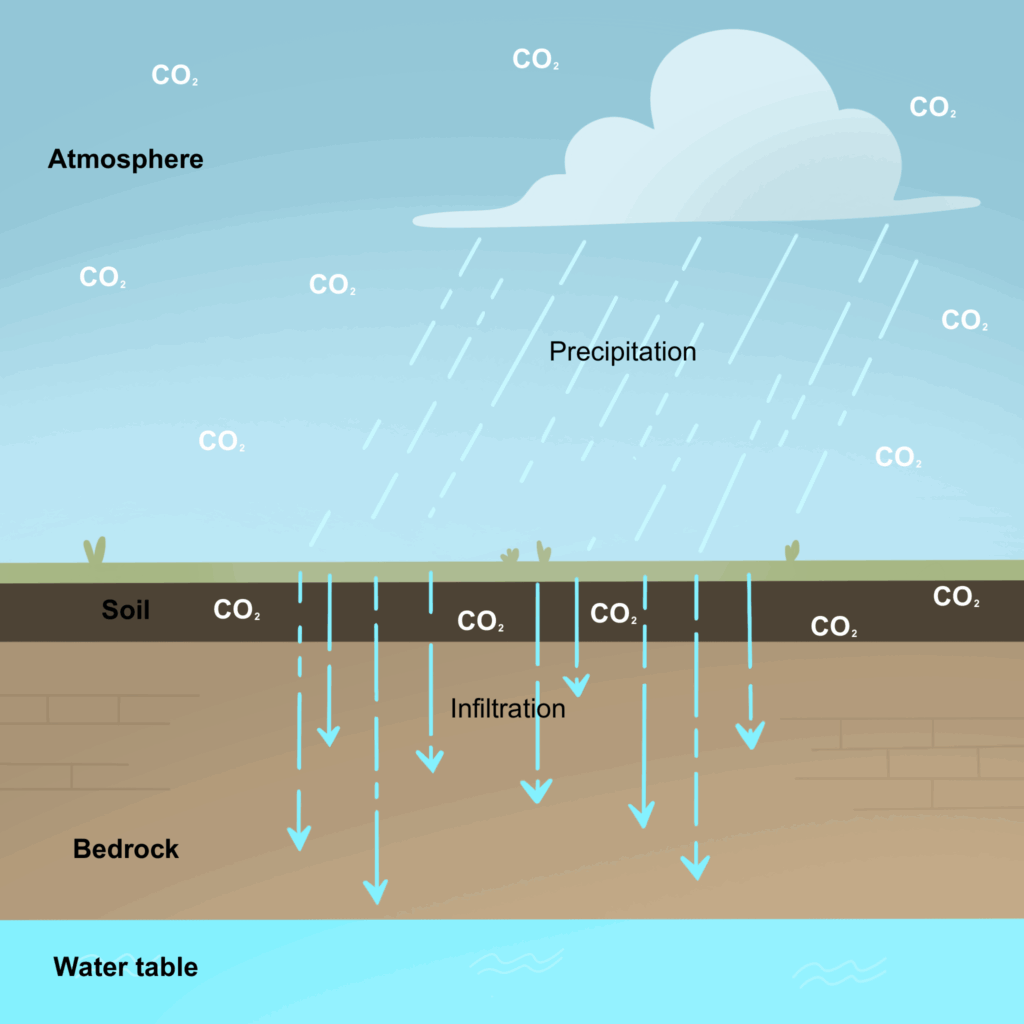

Cave of the Mounds is a solution cave,

which means that it was dissolved out of the rock by acid. This acid is usually carbonic acid, which is relatively weak–it’s the same thing as carbonation!–but can dissolve limestone slowly over time. It comes from precipitation like rain and snow: as water passes through the atmosphere and then the dirt, it picks up carbon dioxide and becomes acidic.

The top layer of the water table (the fully saturated layer of rock beneath the ground) often becomes acidic due to this precipitation, providing even more constant dissolving of the rock.

Weaker rocks are easier to dissolve, so the caves within tend to be larger; likewise, stronger rocks are hard to dissolve, so caves can’t grow very large if the rock is too hard. Our rock is on the harder side, so Cave of the Mounds can’t grow very easily; it’s taken 1.8 million years to grow as large as it is!

Cave of the Mounds, like many caves, features a large fissure-crack in the middle of the ceiling which would have made it very easy for acid to get into the rock and create the space. Today, the cave is hardly getting any bigger; in fact, it is actually getting smaller as more and more cave formations grow!

Once a cave is created, it needs decoration. The problem is that cave’s tend to form at the water table, but formations cannot grow when the cave is filled with water. Luckily, rivers and streams on the surface slowly cut through the landscape, digging deeper and deeper valleys and take the water table down with them. Eventually, the water table drops below the level of the cave and leaves it filled with air.

Now, a new stage in the cave’s life can begin.

As surface water seeps through soil and rock,

it dissolves a small amount of calcite (again, the main component of limestone). The pressure of the rock around the water keeps that tiny bit of calcite in the droplet until it enters the air-filled cave. Once the mineral-laden water drop enters the cave, the calcite precipitates out in the form of speleothems: cave formations. Each drop of water entering the cave leaves behind calcite crystals on any surface they touch.

OVER VAST AMOUNTS OF TIME, crystalline chandeliers of stalactites began to decorate the ceiling, towering piles of calcite rose above the floor as stalagmites, and flowstone hung like curtains from the walls and coated the floor in a blanket of stone.

Those with keen eyes can spot small but ever-present formations known as oolites (cave pearls) that hide in pockets and small pools of water within other formations and form as small sediments are encased in calcite.

In the latter half of the cave, cave coral lines the perimeter of the rooms, indicating a once-higher water level in the area. Shelfstone also shows us past water levels in areas like Surprise Cave, appearing as a horizontal line across the stalactites within.

Some other formations include:

- CANOPY: Form when the base material (silt, clay or gravel) is washed out from underneath flowstone leaving an unsupported, hanging deposit.

- CAVE CORAL: A general term for speleothems with branching stems and nodular tips. Usually formed by seeping water. Often resembles sea coral, broccoli, or cauliflower in appearance. Also known as cave popcorn.

- CAVE PEARL: Deposits formed around a sand particle or other mineral fragment. The particle becomes encased within mineral layers that slowly build up into rounded pearls. Also called Oolites.

- COLUMN: Any formation connecting the ceiling to the floor in an unbroken mass.

- FLOWSTONE: A surface coating of mineral deposited by water flowing downwards from a source.

- HELICTITE: Small twisting calcite structures that project from the walls of other cave deposits in curiously shaped, fragile forms. Thought to be formed by pressurized water within the stalactite seeping through a crack in the formation.

- RIBBON STALACTITE/CAVE BACON/DRAPERY: Forms when a drop of water flows down an inclined ceiling and deposits a ribbon-like trail of minerals that is often thin, banded and translucent.

- RIMSTONE DAMS: Cave deposits which dam water on cave floors. They usually occur in a series of curved steps that hold back water in crescent-shaped pools. Water normally overflows from one pool to the next.

- SHELFSTONE & CAVE RAFT: Form from a thin floating film of mineral on a cave pool. If the surface of the water is disturbed, the cave rafts slowly sink to the bottom of the pool. At the margins of some cave pools, deposits attached to the wall grow out over the water, creating a shelf.

- SHIELD: Form where water seeps into the cave through the ceiling, wall or floor and are semicircular in shape and attached along its straightest edge.

- SODA STRAW: A thin-walled, hollow stalactite that lengthens as minerals are deposited in a ring (at the edge of a drop of water in contact with the ceiling of the cave).

- SPLASH BASIN: A cup shaped ridge deposited on a stalagmite from dripping water.

- STALACTITE: A deposit that grows downward from the ceiling of a cave.

- STALAGMITE: A deposit that grows upward from the floor of a cave.

Regardless of the type of cave formation growing,

each one takes thousands of years to achieve sizes like those inside of Cave of the Mounds. Within our cave, the growth rate of formations ranges anywhere from 50 to 150 years for a single centimeter, but this varies heavily between caves and depends on the cave’s location, the time of year, and precipitation rates.

In total, Cave of the Mounds measures 1,692ft including all rooms, cracks, and crevices. To date, any efforts to find more cave or connections to other caves have been unsuccessful; however, due to the nature of our geologic landscape, it is almost a certainty that more caves exist nearby.

While we may dream of untold treasures and caverns, we strive to cherish the beauty of the cave that has already been revealed to us. Cave of the Mounds deserves to be treasured and shared for generations to come, but in order for it to be appreciated in the future, it must be carefully preserved.

We follow the caver’s motto:

Take nothing but pictures, leave nothing but footprints, kill nothing but time.