Long ago, before dinosaurs ever roamed the Earth,

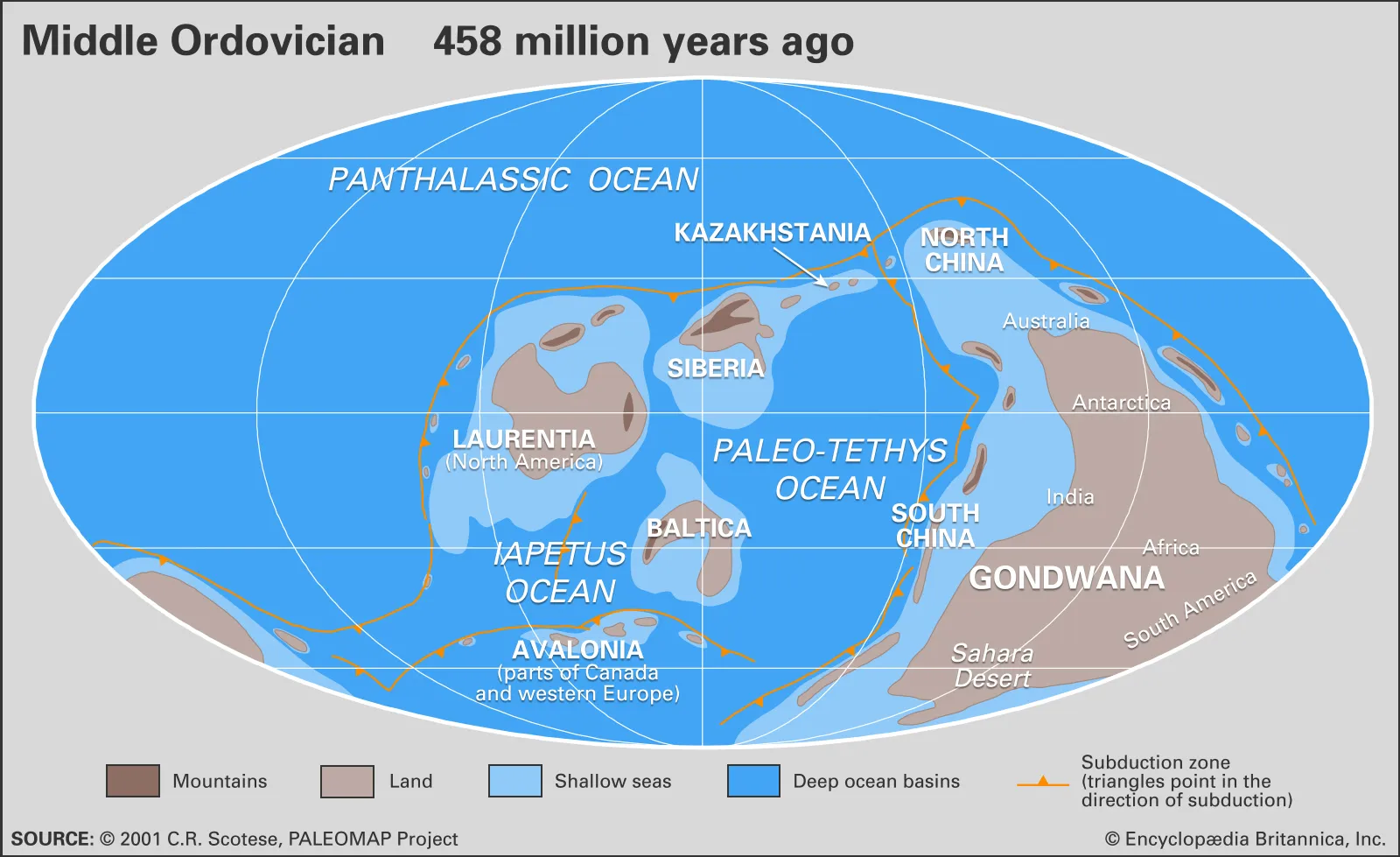

Wisconsin–or rather, the place that would become Wisconsin–was a tropical paradise. During the Ordovician period around 485 million years ago, North America was a part of a large supercontinent called Laurasia which sat right around the equator and had a warm, humid climate.

During this time, most of the Laurasian continent was covered by a shallow sea that was around 70 feet deep. Because of this, a thick layer of limestone can be found throughout North America.

Limestone is a sedimentary rock that forms when shells, corals, and other calcium-heavy debris fall to the ocean floor, get covered in sediments, and dissolve over time. This dissolution allows the calcium carbonate to seep into the ground and solidify, creating the hard rock that we know today. Therefore, this calcium carbonate, or calcite, is the most abundant mineral within limestone.

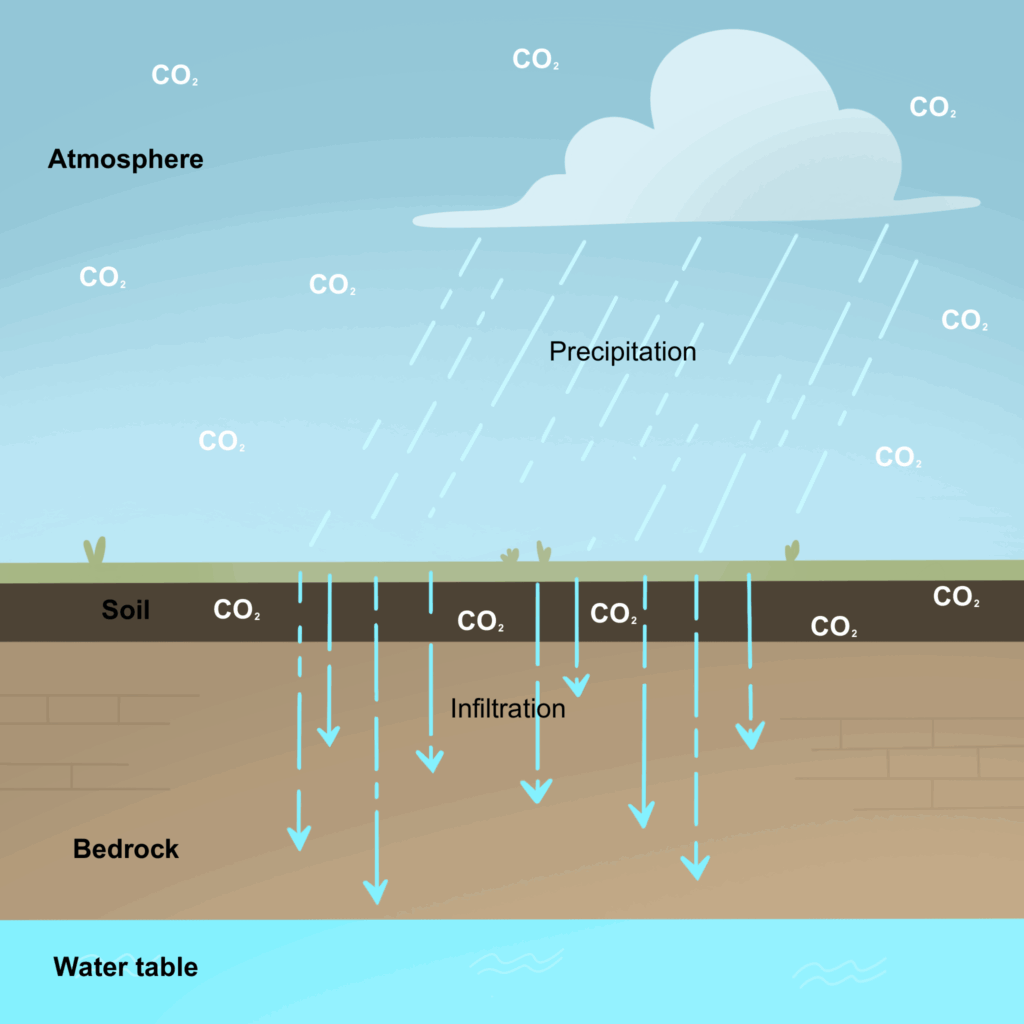

When rain water passes through the atmosphere and then the topsoil, it often encounters carbon dioxide (CO2). It will combine with the CO2 and create carbonic acid, a very weak acid also known as carbonation (i.e. what makes the bubbles in soda pop). Despite being rather tame, it is very effective at dissolving limestone and creating cavities within the bedrock: caves.

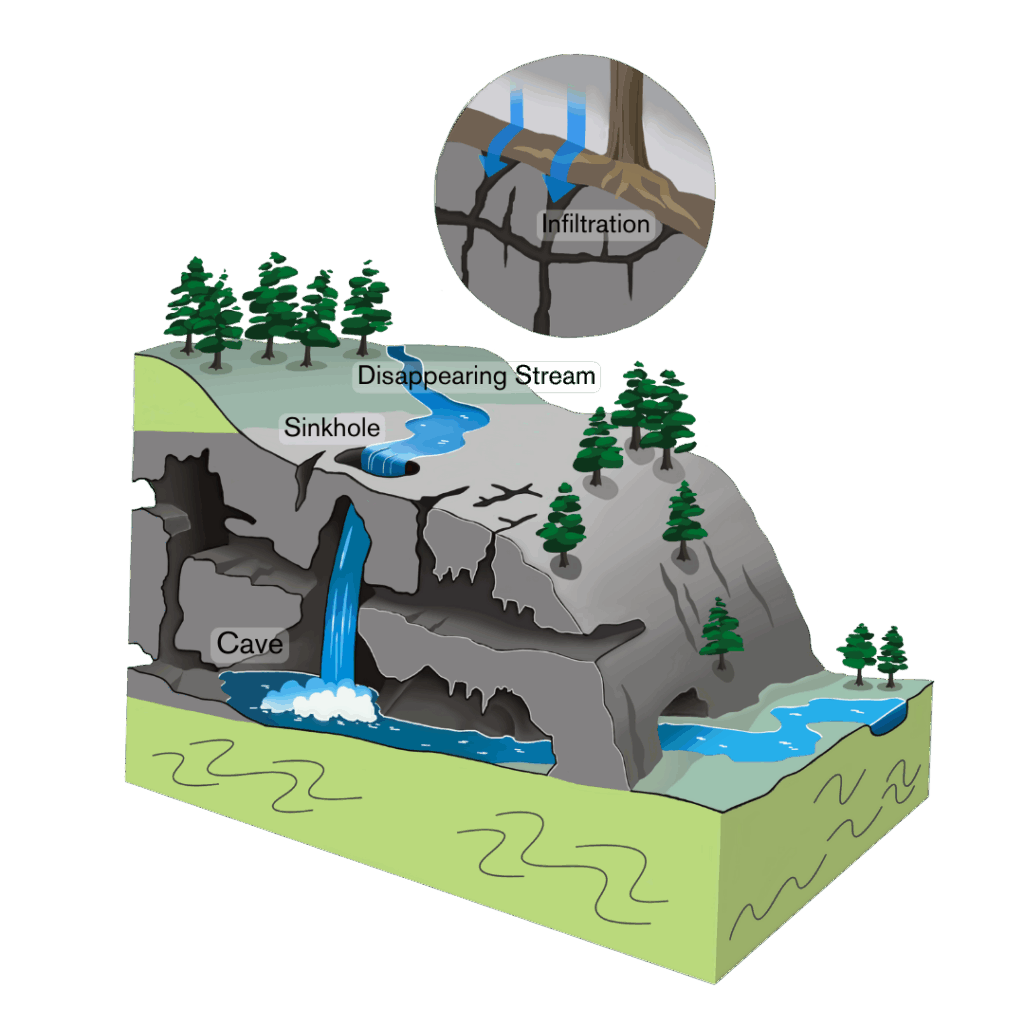

Landscapes that are composed of rock that is filled with cavities are referred to as having karst topography. The caves that are formed beneath the surface in these landscapes are not always as large or grandiose as Cave of the Mounds; often, they are nothing more than a small cavity, but they are abundant. Karst landscapes are also well known for often containing resources such as gas or oil.

Throughout the world, the most common type of cave is a solution cave. A solution cave is a cave that has been dissolved out of rock in the manner described above. The way that these caves form is simple: carbonic acid infiltrates the rock through cracks or pores.

As the carbonic acid slowly moves down through the rock, it eats away at the minerals within the limestone and carries them away. Over time, the cavity within the rock grows larger and larger and will often eventually begin growing formations, or speleothems, throughout. For Cave of the Mounds, studies have shown that this cave formation process began approximately 1.8 million years ago.

Sinkholes and disappearing streams are also common in karst topography and are the direct result of cavities forming beneath the surface. Sinkholes will form when a cave ceiling becomes too weak to support itself–usually because the cave comes too close to the ground surface–and collapses downwards.

Occasionally, these sinkholes will cross the path of flowing water, causing the stream or creek to flow downwards into the cavity beneath the surface. These disappearing streams can flow for up to several miles underground, and occasionally resurface later downstream.

The underside of a sinkhole is usually a collapse.

A collapse is an area within a cave where the ceiling and walls have come down, sometimes forming a large stone pile that reaches all the way to the ceiling. There are two collapses within Cave of the Mounds: the south end collapse and the north end collapse. The north end collapse is very old and is covered by the painted waterfall flowstone. The south end collapse on the other end of the cave has been the subject of research interest since the 1960s. Researchers excavated an ~60ft long tunnel past the south end collapse in order to see if they could access the cavern that it hid. Aside from a few feet here and there, these efforts did not bring up anything substantial.

There have been several studies

conducted at Cave of the Mounds in order to accurately determine the extent of the cavern. In the 1970s, resistivity testing was performed on a location grid around the park.

Resistivity testing calculates how well certain ground layers conduct electricity, and the conductivity of the layer tells researchers what the layer is made out of as different materials handle electricity differently. In their study, they concluded that natural potential (NP) lows indicated open areas (caverns) beneath the surface. While they didn’t find much of anything around the circumference of Cave of the Mounds, they did note several NP lows on the study site. This means that there are several caves and cavities beneath the surface around the Cave of the Mounds park grounds that are separate from the main cavern. This is unsurprising, as Wisconsin alone has over 400 known caves and likely many more undiscovered.

Aside from the testing done above ground, a lot of research has also been conducted below ground. Most recently, Dr. Cameron Batchelor from UW-Madison conducted a research project that took samples from the speleothems growing within Cave of the Mounds and performed several tests that gave us insight into the paleoclimate of Wisconsin.

From her findings, she was able to tell not only the rainfall patterns throughout the seasons, but also the average temperature in the area. This test also gave us an upper limit for the growth of our speleothems: the oldest is a stalagmite in the South Cavern that is ~257,600 ± 2,200 years old. The youngest formations are those actively growing today and are especially visible in the man-made tunnel that runs parallel to the cave in the eastern caverns.

Want to learn more?

Check out our other pages below!